Item: W2497

Watch's origin: Swiss

Number of jewels: 15

Manufacturer: Misc. Swiss

Type of Watch: Wrist

Type: Open-Face

Lug Width: 22mm

Dimension: Approx. 36mm lug-to-lug by approx. 32mm wide

Composition: Silver

Other Attributes:

Military

Wire Lug

Price: $1,995.00

Birth of the Air Service and a most extraordinary timepiece

In the early 20th century, while the major powers of Europe rapidly advanced their military aviation capabilities, the United States lagged significantly behind. This disparity can be attributed to among other factors, the monopolistic influence of the Wright Brothers over early aircraft design in the U.S. Their designs, although groundbreaking, remained relatively primitive and unsafe. High-profile military crashes involving Wright Brothers' aircraft discouraged further development and innovation within the U.S. military, which primarily viewed aircraft as tools for basic reconnaissance rather than for combat or strategic superiority.

Visionaries and Early Experimentation

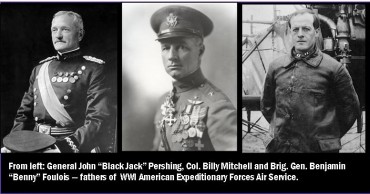

Despite the slow pace of advancement, several American visionaries saw the potential of air power. Figures like young Signal Corps officers Billy Mitchell and pilot Benjamin Foulois as well as aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss were convinced that the future of warfare would be dominated by air superiority. However, it wasn't until the U.S. Army used Curtiss "Jennys" during the Mexican Expedition that military leaders began to see the practical benefits of more reliable aircraft.

Despite the slow pace of advancement, several American visionaries saw the potential of air power. Figures like young Signal Corps officers Billy Mitchell and pilot Benjamin Foulois as well as aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss were convinced that the future of warfare would be dominated by air superiority. However, it wasn't until the U.S. Army used Curtiss "Jennys" during the Mexican Expedition that military leaders began to see the practical benefits of more reliable aircraft.

During the Mexican Expedition, General John "Black Jack" Pershing needed effective reconnaissance over the rough desert terrain. He turned to the Signal Corps, giving Foulois and his pilots an opportunity to test their planes in a real-world combat environment. Although the aircraft faced significant challenges, Pershing witnessed their potential as effective combat tools.

The Aero Club of America and Advocacy for Air Power

The Aero Club of America played a crucial role in advocating for military aviation. Their open letter on July 29, 1915, called for increased funding and support for military aeronautics, highlighting the dire state of U.S. air capabilities compared to European nations. This advocacy helped raise awareness among military leaders and politicians about the importance of developing a robust air force.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, the country was thrust into a conflict where air power had already become a critical component of military strategy. Pershing, arriving in Europe, was struck by the advanced air commands of the Allied nations. Recognizing the gap in capabilities, he summoned Foulois and tasked him with learning from the Allies to bring the U.S. up to speed in aviation support and reconnaissance.

Billy Mitchell, who had been in Europe for a year, observing and learning from the French Air Command, emerged as a key figure. Fluent in French and unbound by specific responsibilities, Mitchell absorbed valuable insights into air strategy and operations. Foulois, a skilled pilot but not a natural leader, complemented Mitchell's renegade and visionary approach.

Differing Philosophies and the Path to Air Superiority

Pershing and Mitchell held differing views on the role of aircraft in warfare. Pershing saw them primarily as tools for support and reconnaissance to assist ground troops. In contrast, Mitchell believed in the potential for air superiority to decisively impact the outcome of battles by direct attack behind enemy lines. Despite their differences, Pershing recognized the backward state of U.S. aviation and initiated efforts to import personnel and knowledge from the Allies.

Mitchell's vision of air superiority began to take shape through the formation of the Air Service. He planned and led significant air operations, such as the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, which demonstrated the potential of coordinated air-ground offensives. Pershing's pragmatic approach and willingness to learn from the Allies ultimately allowed the U.S. to make significant strides in military aviation.

WWI had dragged on for three years with no direct involvement from the United States until the April of 1917 when Woodrow Wilson, along with chief military strategists formally moved to join the conflict in Europe. Informally, U.S. military strategists had observers within the war effort, gauging the military tactics and strength from all sides. Wilson tapped Pershing to command the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe. Upon Pershing’s arrival, he was briefed by Lt. Col. Billy Mitchell on the surprising power, organization and effectiveness of European air forces. At that moment, Pershing realized the U.S. was woefully behind military air power and had to bring itself up to speed – literally. By May of 1918, at the direct behest of Pershing, President Wilson created the Air Service, replacing its relatively anemic precursor in the Signal Corps. Thus, the American Expeditionary Forces Air Service was born.

Pershing, Foulois and Col. Mitchell assigned three tasks to Air Service personnel: create a world-class air force by building planes and bases; fight alongside war-ravaged Allied French, British and Italian forces – and learn everything you can from everyone you can, including the Germans.

Enter Sergeant Weaver

Relatively late in the war – June 22, 1918 – Sergeant Marshall D. Weaver departed the U.S. for France. He was part of a motor mechanic’s regiment of the Signal Corps that would become part of one of the first Air Service battalions. By the time he arrived in France, the role of Sgt. Weaver, along with other members of his regiment, was to assist and learn from the French every aspect of air power. Also, Sgt. Weaver was given a second, more unusual assignment: He was stationed at the Fiat plant in Turin, Italy to observe and assist in engine and airplane manufacture, including the production of the Fiat A. 14 , an Italian 12-cylinder, liquid-cooled, V-aero engine of World War I. The A. 14 held the distinction at the end of the war of being the largest and most powerful aircraft engine in the world at the time.

Of roughly 78,000 Air Service/Expeditionary Force personnel ultimately serving in WWI, only 342 were stationed in Italy and only a handful at the Fiat Turin facility. Sgt. Marshall. D. Weaver was one of them.

While we don’t know much about Sgt. Weaver after his short time in Europe during WWI, we do know he was intensely proud of his involvement in the newly-formed AEF Air Service – so much so that he treated himself to a relatively high-grade, newfangled gadget called a “wristlet watch.” Just like the airplanes being born around Sergeant Weaver, his watch was and is a beautiful, early work of tactile art.

It is a wire-lugged, cushion-shaped time-only piece cased in solid coin silver. Measuring approximately 36mm lug-to-lug by approx. 32mm wide, not counting the crown, it is a handsome, substantial thing. On the back is one of the most wonderful examples of military service engraving we’ve had the privilege to represent in all the many years we’ve been horologists. There, engraved by a remarkably gifted hand, is: “Serg. M.D. Weaver/AEF/1918/Air Service/France Italy” with the winged propeller that is the early and specific insignia of the AEF Air Service.

We have done absolutely nothing to this work of art, save fit it with a faithful recreation in period leather of the strap that likely would have been worn on the piece. I am amazed and humbled by the watch, as its aura is absolutely palpable. And as I write this, the old girl still keeps surprisingly good time. It is truly original in every sense of the word.

I encourage you to enjoy the images of Sergeant Weaver’s watch and to learn as much as you can about the beginnings of air warfare and early aviation. Please feel free to message me with any information or insight you might have about anything related to early flight, the Signal Corps, WWI aviation or military history in general.